Theater J’s Hampton Years

Vision and Courage in the World War II South

Jacqueline E. Lawton is a playwright of growing renown—a 2012 Theater Communications Group Young Leaders of Color award recipient and a member of Arena Stage’s Playwrights’ Arena. In The Hampton Years, she has taken on a vast challenge. Spanning a seven-year period from 1939 to 1946, the play explores the beginnings of an art department at the Hampton Institute—a vocational school for African American students in Southern Virginia. Lawton maps out the founding of the department by Viktor Lowenfeld, a Jewish educator forced to flee a Nazi pogrom in his native Vienna, and the effect of his instruction on two African American artists who thrived at the institute—Samella Sanders Lewis and John Biggers.

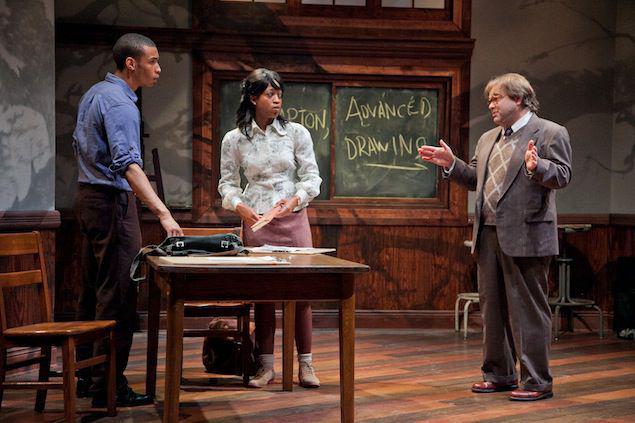

Theater J’s production of The Hampton Years, at its most compelling moments, examines the young artists’ relationship to what they are creating. Lowenfeld instructs with passion as he implores John Biggers, “Draw yourself into the line. Put your sweat and fears into the line. Put the strength of your arms and legs in the line. Put your hopes and longings into the line.” Biggers dissolves into tears, and proceeds to create a compelling sketch of an injured soldier. Lowenfeld’s lesson: “remember, it isn’t enough to draw figures and shapes. If you can’t feel it in your body, your heart, then you can’t put it here on the canvas.”

The scene resonates for anyone who identifies as an artist, and offers a glimpse into what needs further development if we are to feel the full possibility of the play. The focus of The Hampton Years is primarily on Lowenfeld. But his character is never fully fleshed out. The play’s energy concentrates around the two young artists.

By staging The Hampton Years, Theater J has weighed in on another glaring imbalance, as well. In a city with an African American population of fifty percent, only fifteen percent of the works on stage this season were authored by African Americans. Women’s work accounted for eighteen percent of the plays produced, and work by women of color constituted four percent of the offerings.

In an interview with DC Theater Scene, Lawton reveals that her own enthusiasm for the piece rests with the story of the artists: “To witness how much these artists had going against them, and to see their works of art as essential to the community and to what they overcame….that’s a theme anyone can latch onto and feel spirited about.”

She’s right. The artists’ struggle is where the passion lies. The play might have been more successful if it had hewed more closely to Biggers and Lewis’ struggles and triumphs, rather than following the relatively mundane difficulties of a professor attempting to establish a new department. Lowenfeld clashes with the college’s board of directors, true— there is conflict—and dispute to some degree resides in the administration’s belief that blacks cannot be successful as artists. As the college president tells him, “Viktor, if you tell them that they can be artists, they’ll hate you when the world tells them they can’t.” But Viktor’s struggles with the board also involve questions of money, college prestige—the usual academic fare. And although Lowenfeld’s extended family in Vienna is eventually killed by the Nazis, his day-to-day wrangling with bureaucracy, and his efforts to write a book on artistic development in children (he sits at his desk and intones the prose) provide a less compelling contrast to what’s happening around him.

In the play’s best moment. Samella is sculpting a mother holding a child. Lowenfeld tries to tie a blindfold around her head, pushing Samella to rely less on sight in her work. In one of the play’s few defiant moments, she snatches it off, and we’re drawn to the tension. Will she allow her vision, in every sense of that term, to be taken away from her? In the end, she does. She trusts her teacher. She submits, tying the blindfold around her head herself. Of course, she is edified by the experience. The play is about the process of being mentored, about learning and trusting others who are both like us and not.

Robbie Haye’s set works well, converting easily from Lowenfeld’s home to the school, where scenes takes place under the shadowy reach of an enormous oak. While keeping in mind the Emancipation Oak—a large tree at Hampton under which Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation was read for the first time in the South—the shadowy branches that spread across the walls also evoke lynchings, keeping the past and a dangerous present continually before us.

The Hampton Years was commissioned by Theater J as part of its Locally Grown Festival, a unique and vital effort to develop and produce the work of DC-area playwrights. The initiative addresses a troubling imbalance—although more than 240 playwrights live and write in the DC area, their work accounted for only15 percent of the plays performed on DC stages in the 2012-2013 season. Most of the newish plays produced in DC are imports from New York that have already had successful runs.

By staging The Hampton Years, Theater J has weighed in on another glaring imbalance, as well. In a city with an African American population of fifty percent, only fifteen percent of the works on stage this season were authored by African Americans. Women’s work accounted for eighteen percent of the plays produced, and work by women of color constituted four percent of the offerings.

While aspects of the script need ironing out—par for the course for any play in a very early phase of development—The Hampton Years is worth the effort. Giving space and resources to emerging black artists to express the world as they see it—watching this in one of DC’s foremost professional theaters, in an audience comprised of African Americans and whites—provides an unfortunately rare opening. The play works its way into our minds and hearts. It deserves more honing and further productions.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

With all the healthy howling going down around another recent NewCrit essay (http://howlround.com/americ..., let's take a second to applaud this estimable piece of holistic criticism, which provides research into a playwright's intention, survey of the local cultural producing landscape, plenty of journalism as to what's new in this world premiere, and perfectly valid subjective criticism of what might be stronger in a next version of the play in question. All in 930 words. The piece could have been more incisive perhaps in challenging the theater--and the theater even more transparent--in pointing out that after over 120 productions, and 39 world premieres, and plenty of penetrating discourse (apparently) on race and other socially/politically- engaged matter, the producing institution--Theater J--a culturally specific joint with a mission to "celebrate and investigate the distinctive urban voice and social vision that are part of the Jewish cultural legacy" was producing its first mainstage offering by an African-American playwright. After 20+ years in Washington DC. How's that for a lead? We buried it the entire time, never quite reckoning with the fact that after plenty of readings, workshops, presentations in other spaces, we were finally ushering an African-American voice onto our stage for a 5 week, 28-performance run to tell the twinned and intertwined narratives of African American emerging artists and a Jewish Refugee artist educator and his wife, and we were telling it not from the white/Jewish point of view. "Took long enough," a more impudent critic might have written. But tone control was firmly in place, and everyone's best intentions were being honored, even as the situation on the ground for under-represented writers remains rough in Washington DC, and elsewhere. Bottom line, we're on the right path, but it's taken a while to get our engagement trajectory lined up with our art and our artists. So we appreciate the journalism, the criticism, the patience, and the push to get the art even better, as we keeping making strides to expose our audiences to a true multiplicity of perspectives. Keep paying attention and holding our feet to the fire and our art and our artists accountable. Good piece.

Ari Roth

Artistic Director

Theater J

www.theaterj.org

Excited to see what comes next with Jackie's play, Jackie's writing generally, and Theater J's continued efforts at supporting the work of local playwrights through development and production. This question of locavore theater and the role/responsibility/accessibility of local resources to a region's emerging artists- writers in particular- is a huge one for the field. We can all learn a lot from your efforts, Ari. I have real confidence that the DC theater community will gain strength and impact as a result of this initiative and your leadership.