Cal Shakes' American Night asks, "Whose America?" and also, "Whose theater?"

In the past few years, California Shakespeare Theater, under the direction of Jonathan Moscone, has been moving toward being as much about California as it is about Shakespeare. No more does the thirty-nine-year-old company, which is housed in an amphitheater in the Berkeley hills, devote its seasons to four Shakespeare productions (or three, with a Shaw thrown in). Its recent programming reflects a new mission: to explore the cultural and artistic diversity of the Golden State.

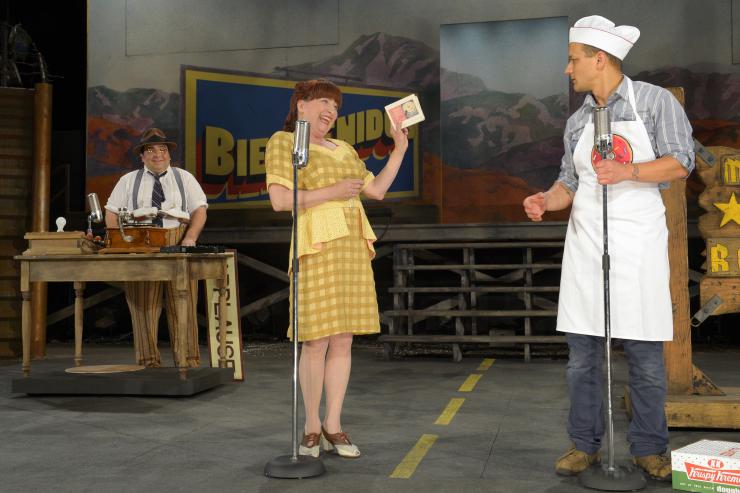

While the company had been creating new work as early as 2003 with the founding of its New Works/New Communities program, it wasn’t until 2010, with Octavio Solis’s adaptation of John Steinbeck’s The Pastures of Heaven, that a world premiere made it to the mainstage. Since then, seasons have been increasingly innovative, and this year that tradition continues with American Night: The Ballad of Juan José, which chronicles the cram session-induced dreams of Juan (Sean San José), a Mexican immigrant on the eve of his American citizenship test. The play was written by Richard Montoya and developed by Jo Bonney and Culture Clash, which Montoya cofounded. Created in 1984, the Chicano-inflected Culture Clash specializes in broad physical comedy and satire; a perennial focus of its criticism is the way Anglo-Americans stereotype or marginalize other groups, but members also poke fun at themselves and their own culture.

Many theaters want their audiences to be less old and less white in order to both have a more sustainable source of ticket buyers and to better reflect their communities.

Looking around at the audience at any given Cal Shakes performance, you can see why the company is expanding its offerings. Many theaters want their audiences to be less old and less white in order to both have a more sustainable source of ticket buyers and to better reflect their communities. But with Cal Shakes, defining community isn’t easy. The company is near “Berserkely,” famous for its diversity and progressivism, but “near” is a relative term. Suburban Orinda, where the theater is actually located, was 82.4% white in 2010; it’s most famous for its leaf blower wars.

Of course, it’s wrong to think of a theater’s community as limited only to its town, but Cal Shakes doesn’t exactly get a lot of foot traffic. It’s located on a highway, and if you don’t have a car, you have to take a train and a bus to get there. And once you arrive, there are other, subtler signs that this is a theater for elites only. Groups with five-star picnics take all the picnic tables, which can actually be reserved if you are of a certain subscriber status, more than an hour before performance. Certain theater seats have blankets waiting on them, while everyone else must pay to rent them. And at the lengthy section on corporate sponsorship during the curtain speech, everyone knows just when to shout, in unison, “Peet’s Coffee & Tea!” along with the speaker. In all these ways, factors both intrinsic to Cal Shakes’s location and perpetuated by its culture contradict the company’s rhetoric about audience engagement. In reality, it’s the kind of theater where, if there’s an interactive exhibit outside the theater (as there is for American Night), the company must instruct audiences to interact with it; at a recent performance, the employees tasked with this unenviable chore looked uncannily similar to bright t-shirt-wearing, clipboard-wielding Greenpeace employees.

This is all to say that American Night is not the most obvious choice for Cal Shakes. The show does feature a few moments of biting satire that almost anyone could enjoy, as in a scene about the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, when President James K. Polk (Dan Hiatt) says, “Weep not, large Mexican gentlewoman,” to a character in a chintzy indigenous costume (Richard Ruiz, spectacular in drag) idly pushing a floor waxing machine about the stage. But as the show progresses, the sight gags become more frenetic and desperate, thinly justified by the play’s “anything can happen” dream structure. It’s Telemundo on steroids for an audience on Metamucil.

Montoya’s point here is that the history one must absorb and recite to become a citizen is precisely the history that makes immigrants second-class citizens in the first place—an important if well-established idea, but one that Montoya asserts too didactically. As Juan progresses through different scenes in American history—from Lewis and Clark to a Texas border town in the early 1900s to a WWII internment camp all the way up to the present, characters explain who they are in stand-and-deliver format, with lines practically lifted from the dramaturgy section of the program. That history lesson is the extent of the story. And Moscone, who directs, often fails to clarify tone; it’s inconsistently dreamlike and inconsistently comedic. Staging, too, baffles. Toward the end of the play, at a contemporary town hall meeting, characters screaming into microphones swarm the stage and mill about like an unchoreographed crowd; they have no clear physical relationship to their setting or to each other. Here and in many other parts of the play, it’s as if Montoya thinks that a few good jokes and a criticism of officially sanctioned history obviate the need for story or clarity.

In mounting American Night, the theater is rightly paying attention to broader societal trends and trying to be a part of them.

But this is not to doom all of Cal Shakes’s efforts at diversification. In mounting American Night, the theater is rightly paying attention to broader societal trends and trying to be a part of them. And it’s important to remember that at large, well-established theaters the pace of change can be glacial. It can take five years of doing talkbacks, for example, before audiences start coming to them in significant numbers. Going forward, Cal Shakes, like all theaters, has a huge question to think about: As your audience changes, to what extent do you cater to longtime supporters and to what extent do you cater to new ones? And does what you say match what you do? If you try to please everybody, you might end up with mush.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

While I'm super happy that all the white people are having a sensible and logical convo and even agreeing to disagree I need to go back to a few of critic Janiak's comments regarding my play: that she felt "raked over" is a real badge for me - its weird that a Tea Party member who stormed out of OSF's version essentially posted the same comment and though I recognize the critics intelligence and sensitivities I find her take on American Night and why it was even performed at Cal Shakes to be full of patronizing entitlement and in the same tone as the many hipsters I meet in the Mission District who prefer cultural tourism over cultural authenticity -

and by authentic I mean me - a native Californian obsessed with the final gasp of the Westward Expansion and the ghosts of Manifest Destiny in every corner micro/gastro pub and high end free range eatery in the inner Mission District of San Francisco. If Janiak is a "new critic" for the Bay Area then where are the new ideas and open minds that not just make room for work of colour for anglo subscribers but work that insists on being given a platform at places called "CAL Shakes" or Oregon Shakes - we built the west - can we dream in it? Can we perform in it? Can we allow the immigrant his dream?

Thank God Jon M, La Jolla Playhouse, Taper and OSF say we can!

I am not concerned one iota that any critic feels "raked" I am concerned that Immigrants will die in the Sonoran Desert this year ON THE AMERICAN SIDE! My work is broad? Over the top? What is Sheriff Arpaio? A nuanced bard with six shooter and a badge? American Night is a highly nuanced piece as well - tho not many critics get this (thankfully the NYTimes did!) From the Sacagawea Camp to the Viola Pettis Camp to Camp Manzanar this ain't your grand pappy's history nor his history book. It is a post modern sampling and mixing in OUR hands taken from YOUR hands that the students at Oakland Tech High School fully embraced and beautifully executed on the weekend of May 1st - (we NEED to hear from them as well). This past weekend we recorded AN for LA Theater Works so that the work will endure and live to rake the next generation of critics. Counter OAK TECH High with the Arizona Attorney General who banned the books of Culture Clash with that of the Bard as well as Black, Women & Queer studies for AZ High Schools and you get the idea of the bat shit crazy south west that gave birth to American Night. Cultural Tourism wants tacos and salt rimmed margaritas not in your face fuck you theater that makes you laugh your ass off and hurt on the way home to your comfy confines.

I remember the thin skinned flabby white mid sections of the New Haven critics at Yale Rep who felt entitled enough to use racists terms to describe NIGHT - "Chinky Face" was one of the more painful - but so was "Black Wet Nurse" of Viola Pettis - (and I know I will be chided for using the work "white" the critics always were - so race is a factor here - the Hartford critic going so far as saying that he was sure the Klansman depicted in NIGHT was not as harsh as I portrayed: "C'mon!" cried the critic.

Look, NIGHT is not a perfect play - never set out to be - it is a work that challenges and exposes and haunts the colonial ghosts of a continent. A new critic is like an old critic and some of the old critics get it and some of the new do not - its all good - just don't expect me to embrace and feel good about all your sensitivities while people are dying in the desert and Obama is detaining women and children in desert detention centers that make Manzanar look like a friendly Swiss Village. Fuck that...

Make room for our work and we will make room for the new critics with their limited yard sticks and thin skin - NIGHT is no mush - it never pleased all - it is meant to haunt the colonial ghosts of a continent - even if those ghosts never die and where hipster garb.

Montoya

I thank sincerely the Cal Shakes production and Social Engagement which inspired the young people and students of the Eastbay - now on to Portland and Texas with an imperfect play aware of its time and place...

So many thoughts on this discussion – here’s my best effort at collecting them.

• The “new criticism” is actually a tweaking of critical journalism from the 80s’s and 90’s, inspired by many gonzo journalists. When I was reviewing music for SF Weekday back in the day, many of is interspersed our personal impressions of the events with more standard reviews. I remember a particular review of a notorious local band that focused on a patron who’d passed out in the audience and was carried out hand-over-hand to the exit. I admire Howlround reinvigorating the form and absolutely support including a reviewer’s experience and reactions to any review, but as we’ve seen it’s a murky path.

I also think it’s bit disingenuous to comment on privilege without copping to whatever level of privilege the reviewer is heir to. Knowing the reviewer is a young Caucasian woman with an Ivy League education changes the parameters of the commentary at least for me.

CLARIFICATION - my point here is that with the "new criticism" the writer's background, perspective and potential for bias are more germane to any discussion than they might otherwise be. As least that was a hallmark of the "old" new criticism....

And this is nothing personal about Lily – I admire her work and her spirit and her passion and personal sense of humor!

• I had the pleasure of seeing Colman Domingo’s “Wild With Happy” at TheaterWorks, a South Bay Area LORT theater that seems to be working diligently to diversify its programming. They’ve also been longtime champions of new plays which is awesome.

They are also subscription based, which is great for them but played out very unhappily at the matinee of Domingo’s work that I attended. My partner and I were clearly the youngest audience members by many years except for a few grandchildren of the subscribers. It was also clear that minimal efforts had been made to educate the typical matinee subscribers as to the nature of the work and its themes and content. An African American gay man drives his dead mother’s ashes to Disney World – most of the audience walked out during the first half of the play and the remainder could be heard talking loudly “what is this? This is horrible!”

What does that experience do for and to the artist? Will someone like Colman Domingo turn down the next opportunity to bring his work to a richer, older, more privileged audience next time around?

So we wind up with a theater that supports newer voices, divergent voices, yet doesn’t do what I would consider important work in preparing their audience for the experience. Compare this to Cal Shakes’ efforts which at least tried to prepare their likely audiences for a new work.

• The heart of my reaction to the issues raised by Janiak’s review and the responses have to do with my general distaste for the non-profit vs for-profit models. If it looks like a duck, quacks like a duck…

I admit I’m not an expert on the fine distinctions between non profits and for profits, but over a certain size m, income and endowment the two run together in practice if not in form.

No one REALLY complains about going to a Bruce Springsteen or Beyonce’ concert and paying $200, $250 etc for great seats and a butt pillow. Yet we cavil when donors to non profit theaters are offered perks in return for their financial support. How else are non-profits supposed to exist?

But what makes a theater a non-profit anyway? Return on investment isn’t at issue? It certainly isn’t always that prices are cheaper, although compared to SHN or Broadway they are.

As long as we keep this (what seems like an arbitrary) distinction, non profits of a certain size are going to have donors who give money to support them over and above the ticket price. With that money available, theaters have a responsibility and even a legal duty to provide educational services to the community, and how an individual theater accomplishes that differs one to the other. For example, ACT, to their credit makes very inexpensive tickets available for all their shows to groups of students, offers them Words on Plays and arranges lectures conducted by the artistic staff.

As an instructor, I find ACT one of the more generous theaters in that regard. They also offer use of their second space at NO CHARGE to community organizations. Who does that? No really, who does that?While one might argue about the lack of diversity in their programming, ACT seems to take their responsibility as a non-profit seriously in terms of community participation.

My point here is that even to a slightly trained eye the differences between large non profits and for profit theaters seem arbitrary and inconsequential. But as long as we make those distinctions, we are going to have to come to terms with the perks that more affluent members of the audience enjoy.

This is an interesting and important conversation between two artists. Is the original review/article a bit "snarky" at times? Perhaps, some terms seem out of Th.Crit 101 but it engendered thought and more conversation- good for both Rebecca and Lily, both gracious and talking TO each other. Please be careful RH not to limit opinions and conversation. Sincerely.

This post by Clayton Lord responds to this thread, and adds some important thoughts, i believe.

http://www.artsjournal.com/...

Rebecca and Lily, thanks to you both for beginning what I think is an important conversation. In the HowlRound NewCrit initiative we’re trying to find a way to talk about the work in context—what I would call criticism. We are not interested in whether our critics like or don’t like something but rather, how they experience the work in the context of knowing their theater community and in exploring the “why” of the play. These aren’t reviews. And hopefully they will spark the kind of conversation that you both have started here.

(But please let me acknowledge as a side note that I think we’re still finding our way, and that criticism in the context of the work is the most controversial thing we’ve tried to do as it elicits such strong emotions.)

I’ve been aware for awhile now of the Triangle Lab and of Rebecca’s work with Cal Shakes and Intersection for the Arts. It’s critical and courageous work and it’s truly at the avant garde of our field in terms of leadership of a large institution committing to real change in the stories being told on stage. I worried when publishing this piece that perhaps that wasn’t stated clearly enough, but I also know that very few people watch theater from the deep insider place that I do.

I was struck when editing Lily’s piece in the real experience of dissonance she was having in relationship to the intentions of Cal Shakes. Having worked inside of many institutions now, this dissonance between institutional intentions and audience experience allow for the most productive kinds of conversation.

Of course the challenge of real change is that it requires such incredibly hard conversations, and it takes time and generosity and openness. It takes a willingness to enter conversations that are painful. And inevitably you will work tirelessly around an initiative and someone will come along and misperceive those efforts or not experience them as you intend. And the most challenging conversation we’re having in our field right now is the one Rebecca and Lily have entered into above. It’s happening all over HowlRound just this week—a conversation about color blind casting in Carla Stillwell’s regular blog about diversity, a conversation about female critics sparked by Daniel Jones’ blog.

How do we tell new stories? How do we make our field, our plays, our theaters, a place that welcomes something other than the established and already committed patron with means to pay for expensive tickets? How do we respectfully deal with what Rebecca calls the “fossils” of old ways of doing business? Everyone is desperate to bring theater to the 21st century.

Thank you Rebecca and Lily for opening the door to more and deeper conversation.

This feels like a really promising dialogue happening around this post. Rebecca-- your response is both empathetic and generous, where it could easily have been defensive and dismissive. I think Lily is pointing at some important questions about the process of transformation at legacy institutions. Cal Shakes has been so tenacious about this transformation that I'm sure it feels bad to see someone saying "you ain't there yet". And, in truth, I feel that the original article reads more like a thumbs-up/thumbs-down, judgmental piece than I'm used to reading here, tonally. The thing about a process is that its not finished yet, and to report on it as though it is is to miss an opportunity to understand the core issues in the experience of dissonance Lily's describing.

I've worked in the legacy world trying to re-invent itself. The attempt itself is to be celebrated, and I am glad time is spent in all the discussion here so far doing just that. I love the idea here that the process of transforming an organization reveals fossils. I have this exact experience- and they are uncovered layer by layer. You pick up, and attempt to resolve, these challenges iteratively, Lily, not in one fell swoop. So dissonance between the stated goals and the current practice is to be expected and reveals the learning edge of the process underway. To me, it is evidence of progress, not of rhetorical or semantic disingenuousness.

From one person daily failing to another, keep at it. Honest effort, productive discussion, and plain old pluck are what's called for. As Lily's comment indicates, everyone on this thread is a learner. And this question of transforming these institutions is so critical to the future of the form that I'd rather a bumpy conversation than none at all!

So, thanks Rebecca, in particular, for making it a conversation. And please keep reporting here on the progress in the process as you go along!

First, kudos to HowlRound for making a stab at something as huge as reinventing criticism. An effort as large and as necessary as diversifying American theatre and finding deeper ways for audiences to engage with the work on stage. And how important to bring in young voices, and especially young female voices -- too often excluded from old crit -- into the critical conversation. And what crucial questions to be asking in this new criticism, questions like why is the work on our stages being chosen, who is it being presented to and why, and what is the total experience for the audience,

And there is much in this article that addresses these important questions, questions not usually addressed in mainstream criticism. All not only good but great.

What is distressing to me in this piece -- and by way of transparency I must say that Lily is a new employee of Theatre Bay Area, where I am executive director -- is a distinct tone of -- and I can find no other word -- a tone of contempt that emerges for so many involved with this production. Most distressingly, the audience. "Metamucil?"

Clay Lord (a recent former staff member of Theatre Bay Area now at Americans for the Arts) wrote an empassioned response to this article on his New Beans blog (see Michael Rhod's comment above), that outlines a number of complaints with this article. I agree with almost all of them. But more, I am disappointed with the author's retreat to snarkiness ("Metamucil," "Greenpeace," suburbanites engaging in "leaf blower wars").

Cal Shakes is doing far more than most theatres -- large or small -- to shake up their programming and reach new audiences. Novick is experimenting with new ways to engage the audience more deeply and more interactively with the work on stage, and Montoya is trying to bring the issues of immigration and what it means to be an American before American audiences. Perhaps they are succeeding, perhaps they are, at times, failing. But they are trying, genuinely, and with a learner's humility, to change the status quo. Nothing in this effort deserves to be met with contempt, and neither does the audience -- whatever their age or color -- who comes to engage in the conversation.

Thank you Brad for this. My thoughts precisely, though more appropriately and eloquently worded.

Wow. More intimidation, and even more direct intimidation than Ms. Novick dared. Poor Ms. Janiak - she WILL be silenced - and so much for HowlRound's supposed critical experiment.

Lily, I want to respond here, and - as the director of Cal Shakes's Triangle Lab, charged with much of the work you're described - would have loved the opportunity to inform your article a bit in advance.

I want to say first that I think it's extremely important to critique institutions who are talking a good game but not delivering, there's so much rhetoric everywhere in our field and certainly a lot of it is hollow. In fact I have engaged in that kind of discussion often both here on Howlround and elsewhere. Having been outside the LORT world for my whole career, I came to Cal Shakes precisely to see if we could make these lofty aspirations a reality, and certainly we worry and wonder all the time if the change is too slow, if the inertia of how we've always done things is too great, if our subscribers will come along for the ride, etc. But I also think that if we (not just Cal Shakes but all of us in the field) want some of the bigger theaters to really change, we have to let them start where they are, with the audience they've got, which means that early steps are going to necessarily take place in a kind of cognitive dissonance between where we have been and where we're trying to go. I have to say that it's hard to exactly grasp your point here, somewhat confusingly embedded in a review of a show -- are you saying that Cal Shakes shouldn't do American Night because it has an audience that seems to you not to match the content of the work? Or that interactive activities shouldn't take place if they aren't organically embraced by the audience without persuasion? I really disagree. How can a theater that, yes like many, has a disproportionately white audience, begin to change that except by starting to change what stories we tell, who tells them, and how we engage audience members in telling their own stories. Changing the work and changing the audience has to go hand in hand and at the beginning of course you will see the kind of disjunction you describe.

I want also to respond to a few of your points specifically, to provide a little context and clarification:

- First, Cal Shakes's performance space is in Orinda, which is a very small suburban town in Contra Costa County. Only 6% of our audience actually comes from Orinda, and less than 50% from Contra Costa. The rest comes from Oakland, Berkeley, and San Francisco, with Oakland being the most represented zip code. You can get to our theater by taking BART just one stop past Oakland, and then a free shuttle which we provide from the BART station to the performance space. That said, of course our location is a significant barrier for many people, and the mismatch of the demographics of our audience with the demographics of the Bay Area is a challenge we are working to address in a myriad of ways. One of the things my program is charged with is creating work that takes place in other locations - not just at our outdoor venue - as a way to shift who sees it and how available the work is in different communities.

- Regarding the interactive activity. This season we created a wall that invites audience members to participate in different ways for each show. Our aim with this is to open people more to the content of the show, to learn more about our audience and let them learn about each other, and to make concrete our conviction that everyone has a story to tell. For American Night we asked audiences to write a "story in a bottle" responding to the prompt "write a one-sentence story of a departure, a journey, or an arrival in which you or a family member left something behind, crossed a border, or started a new life." Over the run we had 370 audience members turn in stories (you can read them here: http://www.thetrianglelab.o... a return I felt was very successful, especially because the range of stories was very, very moving, powerful, and complicated. As I think anyone who does audience engagement work will tell you, it's really important to provide as many paths to participation as possible so we of course had a volunteer tasked with helping people do the activity and encouraged people to participate in the curtain speech.

- About the chairs, the blankets, and the "trappings of an elite theater": here is a place where I completely agree with you. One thing we're discovering as we make change, is that more and more "fossils" of the old ways of doing things get revealed. We have actually been having significant staff discussion over the last couple of months about the ways in which these donor perks operate in contradiction with the participatory culture we're trying to create and we're in the process of re-designing all of that for next season.

- Finally, I want to tell one more story about American Night. On opening night, Favianna Rodriguez, an extraordinary artist and immigrants rights activist, and long-time collaborator with our partners at Intersection for the Arts, came to the show and came up to me afterwards to see how she could help to connect the show with some of the groups she works with, especially undocumented youth. We ended up conceiving two post-show events with speakers from the undocumented community reading stories they'd written, talking about the challenges of life in the Bay Area as an undocumented immigrant, and discussing how their stories connected to the story of the play. With almost no lead time, we had 75-100 audience members stay for both events, and had incredibly rich discussion with and about a sector of our community that has never been represented at our theater before. So sometimes change goes quickly -- especially when you have an audience like ours that is smart, political, and open to change.

Rebecca, Thanks for this response. I appreciate not just your insight, but your civility and grace.

I'd like to first address the format of this article, which has come under criticism here and elsewhere. Is it a review? Is it a feature? I like to think it's both, and if I've failed to combine those two here, that's valuable for me to know. Part of what attracts me to writing for HowlRound's NewCrit section is precisely that: the writing here isn't supposed to look like criticism as usual, which as we all know is often lacking in, well, everything. What NewCrit is trying to do with readers of criticism isn't all that different from what Cal Shakes is trying to do with its audiences: push them toward new forms and see if they'll come along for the ride. If here I have pushed too far, perhaps next time I'll try something different.

I do see my work here as primarily critical (reviews) rather than journalistic (features and interviews), but I believe a critic's purview needn't be confined to when the house lights are down. Criticism ought to take into account the entire experience of theatergoing -- including transportation and first impressions of the space -- because that's what the audience experiences. These things impact how audiences interpret art, and, more indirectly, they influence the kind of art theaters make.

Because I wrote this as a critic of "American Night," not of Triangle Lab as a whole, I chose not to interview you or others from Cal Shakes. In writing, I decided the most valuable thing I could offer would be to describe my experience as an outside observer. I certainly agree with you that I could have provided more context. I feel that way about almost every essay I write. I'm very grateful you took the time to supply it.

To answer your questions, of course I don't think you shouldn't challenge your audience with new kinds of art or engagement, and I'd hoped the end of my article conveyed that. But I also don't think that admirable goals like Triangle Lab's give theaters a free pass from criticism along the way to achieving them, particularly when, as you said, "'fossils' of the old ways" directly contradict words and deeds geared toward the future. Maybe one of the places where we most disagree is in just how important those "fossils" are.

Thanks again for engaging with this piece in such a lively, thoughtful and gracious way. Let's keep the conversation going.

After reading your response, Ms. Novick, I'm trying to see in what way Ms. Janiak's article was inaccurate, for in the end you basically cede her every point. What is quite clear is your desire to gently intimidate her. And it looks like you succeeded.