Dialogue and The Age of Industrial Storytelling (or, A Defense of the Theater)

1

Content.

The industry moniker for stories, which are now fed, like fodder shoveled into a voracious human pipeline, disappearing—almost as soon as they are created—into a global tract more esophageal than spiritual, consumed and digested with a ceaseless fury. To put it so is perhaps to appeal to the strain of apocalypse so prevalent in much of the world’s contemporary stories. The exponentially exploding numbers of consumers and the mind-boggling velocity of the distribution streams aside, perhaps it has always been so. Perhaps it is just another myth to imagine a mystic sheen clouding ancient listeners eyes as they heard tell of Gilgamesh’s exploits in early Mesopotamia, or those further west who may have witnessed blind Homer recount Achilles’s loves and travails. Certainly, we know that the groundlings at Shakespeare’s Globe were not cowed by seriousness. There was no silent awe for the so-called regal goings on above them. And we also know that our great Bard played as fervently to those below him as he did to those above. And that was, after all, the most gilded age of our tongue.

Even then, the dictates were clear: A story must move, through its reversals and recognitions, through its bawdy interludes, through its plodding exposition to the climax and confrontation; and must move in another sense as well: move the audience to laugh, to cry, and most importantly, to pay hard earned money. It would be more than silly not to recognize the hegemony of the formulaic as something perhaps primeval. Likely, there has always been some correlate of an industry then in the matter of story. So what now, if anything, is different?

2

Perhaps we should concede that nothing is different, even if the case to the contrary could be convincingly made. We are storytellers, after all, not historians. What use is it to us or to our audience to waste precious time on stage or screen, or on the page, bemoaning a more perfect past? Aren’t we dwellers of the present par excellence? Isn’t the now our only true and rightful home?

Let us entertain forevermore these possible truths:

That our own polarities might be enduring, even eternal.

That there has always been some form of higher practice of the narrative art, and always been its opposite.

That there have always been artists who aspire to steward conscience, and others who work to manipulate the mechanisms of human attention for baser ends.

An illustrious partisan of this long debate, Jonathan Franzen, called the former artists who aspire to Status, and the latter, those who abide by a humbler Contract with their audiences. And yet, even these accepted antinomies are perhaps not worth our ultimate allegiance. Even Franzen concedes:

To an adherent of Contract, the Status crowd looks like an arrogant connoisseurial elite. To a true believer in Status, on the other hand, Contract is a recipe for pandering, aesthetic compromise, and a babel of competing literary subcommunities. With certain novels, of course, the distinction doesn't matter so much. Pride and Prejudice, The House of Mirth: you call them art, I call them entertainment, we both turn the pages…

Jane Austen and Edith Wharton for him; closer to our time, and to our craft, let us suggest: Woody Allen, Seinfeld and David, Fellini, Wilder, Nichols, a list that could go on and on and on…

3

If that list of narrative artists is heavy with those working in the movies, it is for a reason. The global mass production of story—worth a daily fortune to those who control not only the means of its production, but more importantly, its dissemination—is an industry conducted not in words, but images. The human face, the woman’s body, the sound and fury of gunfire and the attendant blood to which they are heir, all of these dissolve the borders and facilitate a commerce in which the word has all but ceased to exercise its ontic, originating power. The effects are much greater than a shift of creative endowment away from the one who originates—the writer—and to those who reenact—directors/actors.

The human face, the woman’s body, the sound and fury of gunfire and the attendant blood to which they are heir, all of these dissolve the borders and facilitate a commerce in which the word has all but ceased to exercise its ontic, originating power.

Indeed, this hegemony of the image has altered the very nature of the world’s attention. Some have spoken of it as a shallowing…of consciousness, of discourse, of empathy; or as a death...of nuance, of deep thinking, of literary culture; others still posit that we are beholden to our screens like sleepwalkers lost in a waking dream, likening our enslavement to the image to Plato’s parable of human ignorance. For aren’t we all—as we sit in our darkened living rooms, staring at boxes of light—like those who would mistake moving shadows for reality itself?

And though there can be no substitute for a thorough understanding of the state of affairs, there is likely little to be gained in protestations. After all, if we are to ply our trade and to make our daily bread in a world awash with content, the only real issue is to understand our place, our work, our agency. And to this end, I might suggest that only place left for the word in this age of industrial storytelling is that of dialogue.

4

The screenplay is a blueprint, the map of a story, a use of words that evokes, but does not define. It is the art of concoction and insinuation, rigorously delineated by the architecture of genre, but even more so by the pressures of the production and of a global audience’s fickle attention. The story must move—beat to beat, scene to scene—beginning its well-practiced march from introduction through rising action that must not abate—except to allow for the expression, in interlude, of the social pieties germane to the themes at hand—so, through a rising and relentless middle to the inevitable denouement, usually defined not by dramaturgy, but by convention.

The story must move. And its plan must be executed with economy. The screenwriter moves from task to task—setting up expectation, establishing characters and their motivations, artfully conveying exposition, staging climax and conflict—like a slalom skier gliding through the gates. Of the tools at the screenwriter’s disposal, the most obvious, the most relied on, the most abused and the most inspired is dialogue:

Gittes has been in a state of near frenzy himself. Gets up, shakes her.

GITTES

Stop it!—I'll make it easy—

You were jealous, you fought, he

fell, hit his head—it was an

accident—but his girl is a

witness. You've had to pay her

off. You don't have the stomach

to harm her, but you've got the

money to shut her up. Yes or no?

EVELYN

—no—

GITTES

Who is she? And don't give me that

crap about it being your sister.

You don't have a sister.

Evelyn is trembling.

EVELYN

I'll tell you the truth...

Gittes smiles.

GITTES

That's good. Now what's her name?

EVELYN

—Katherine.

GITTES

Katherine?... Katherine who?

EVELYN

—she's my daughter.

Gittes stares at her. He's been charged with anger and

when Evelyn says this it explodes. He hits her full in

the face. Evelyn stares back at him. The blow has forced

tears from her eyes, but she makes no move, not even to

defend herself.

GITTES

I said the truth!

EVELYN

—she's my sister—

Gittes slaps her again.

EVELYN

(continuing)

—she's my daughter. Gittes slaps her again.

EVELYN

(continuing)

—my sister.

He hits her again.

EVELYN

(continuing)

My daughter, my sister—

He belts her finally, knocking her into a cheap Chinese

vase which shatters and she collapses on the sofa,

sobbing.

GITTES

I said I want the truth.

EVELYN

(almost screaming it)

She's my sister and my daughter!

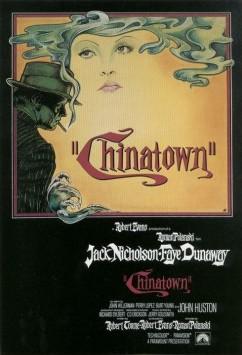

Chinatown (1974)

There can be few moments in the history of screenwriting as startling, as important, as touched with genius as this scene from Robert Towne’s Chinatown, in which Faye Dunaway’s character reveals the horrifying truth of her incestuous relationship with her father, the power broker played by John Huston. And yet, even here, the dialogue, while revelatory, is subject to the pulse of film narrative, in service to the story. Dialogue is never—or perhaps let us say rarely, as in the cases of Preston Sturges or Eric Rohmer or more recently, Tarantino and Sorkin’s The Social Network—an element autonomous enough to compete with story when it comes to the silver screen. And so, for the most part, screenwriters are draftsman, telling those who need to know—designers, directors, actors—about what the story that they, and not the writer, will ultimately be telling the audience.

5

If the screenwriter can be said to use dialogue in service to a filmic sense of story, the playwright is different, working in a form where the spoken word is the fundamental building block, and where all sense of story fundamentally emanates from a mimesis of the human act of communication. And so, if we can say that the screenwriter makes the characters talk to serve the ends of a movie’s blueprint, the playwright allows the characters to speak in order to fulfill the telling of her tale. Indeed, so much of the most important work in the contemporary theatre is an investigation of language, the exploration of what our speaking says about the way we live, the way we think, the way we are. Embedded in the playwright’s aesthetic ideal is an allowing of the spoken word, an almost holy regard for the voice as the initiating element of the process of creation. The creed has probably never been more simply and perfectly expressed than by Harold Pinter in his early text, “Writing for the Theater”:

I have usually begun a play in quite a simple manner; found a couple of characters in a particular context, thrown them together and listened to what they said, keeping my nose to the ground.

Indeed, so much of the most important work in the contemporary theatre is an investigation of language, the exploration of what our speaking says about the way we live, the way we think, the way we are.

The primacy of the spoken word as a gateway into the mystery of character and context is not unique to Pinter. Faulkner is said to have told young writers to trot behind their characters and to listen to what they spoke. This quieting of the writer’s awareness and turn to the internal object is not only an act of humility, it is a coaxing from the depths of something like life itself. An announcement of a willingness to empty oneself in preparation for an inhabitation that is more than an act of conjuring. Almost any writer in the theatre worth any salt at all has had the startling encounter, experienced that numinous moment when a character has suddenly come to life, speaking with words or of things that one barely knows. And so begins the character’s long resistance to the writer’s intentions. And when this happens, the true difficulty begins, and yet, all is well.

6

The character’s resistance is key. And it goes to the heart of the matter here before us. Pinter again, in a passage worth quoting at length:

You create the characters and they prove to be very tough. They observe you, their writer, warily. It may sound absurd, but I believe I am speaking the truth when I say that I have suffered two kinds of pain through my characters. I have witnessed their pain when I am in the act of distorting them, of falsifying them, and I have witnessed their contempt. I have suffered pain when I have been unable to get to the quick of them, when they willfully elude me, when they withdraw into the shadows. And there’s a third and rarer pain. That is when the right word, or the right act jolts them or stills them into their proper life. When that happens the pain is worth having... [There] is no question that quite a conflict takes place between the writer and his characters and on the whole I would say the characters are the winners. And that’s as it should be, I think. Where a writer sets out a blueprint for his characters, and keeps them rigidly to it, where they do not at any time upset his applecart, where he has mastered them, he has also killed them, or rather terminated their birth, and he has a dead play on his hands.

The perspective this passage can begin to shed on the travails of writers working in an industry setting is obvious. The extent to which content is informed by the needs of the larger global appetite appear to mandate a different approach. The foregrounding of genre and story endemic to the film consciousness necessarily tilts the balance in favor of the blueprint, the controlled narrative that hews to the necessary and expected reversals and recognitions. The matter is one of the marketing consciousness. In a world where the distribution channels have become themselves synonymous with the means of production—after all, a writer cannot make a living without access to this ever-expanding, yet oddly more and more homogenous marketplace—marketing has become a central part of the storytelling experience. And invariably, in their attempts to shape the expectation of an audience, marketing departments live and die by a proven truth: It is always easier to sell something known and familiar than something new and unknown, let alone unknowable. And so it is that our industrial stories no longer truly address the evolving Spirit—to choose a defiantly gauche and Hegelian locution—but address themselves to a different modality of our collective identity: The Economy.

7

Does this mean that contemporary audiences themselves wish to be seen primarily as consumers, and not human subjects? A question for which there is no simple answer, but which goes to the deeper matter of our changing sense of who we are as human subjects. Guy Debord, a still-too-little-discussed visionary, described some forty years ago the direction we were eventually to take as a species: Creators of a society increasingly beholden to—and defined by—the image, The Society of the Spectacle, in which individuals increasingly saw themselves as image‐objects fitting into a larger material order. Debord puts it thus:

The Spectacle subjects living human beings to its will to the extent that the economy has brought them under its sway. For the spectacle is simply the economic realm developing for itself... I recall an incident during the latest financial crisis that underscored, for me, the truth of Debord’s observation, and represented a mythopoetic shift in my own understanding of what may be happening to us now. I was walking along the street with a lady friend, when we stopped at the window of a woman’s shoe store. Beside us, a mother and her daughter—who couldn’t have been more than thirteen—were perusing the same display. The mother noted a pair she liked. The daughter agreed. The daughter moved to the edge of the glass to spy the sticker along the back of the heel.

“Two hundred,” the daughter said.

“It’s too bad. They’re lovely.” The mother started to move off. “Hopefully they’ll go on sale.”

“Mom,” the daughter objected, standing at the window, lingering. “You shouldn’t say that. If everyone does that, it’ll be bad for the economy.”

The daughter has internalized the message Debord warned us of forty years ago: that the Economy would consume us; that its well being would end up coming before our own. And that the power of the purchase would become our act of ritual sacrifice, our only holy enaction, performed daily for the sake of this, our new God’s survival.

And that the power of the purchase would become our act of ritual sacrifice, our only holy enaction, performed daily for the sake of this, our new God’s survival.

8

Is it our task as storytellers to service the human subject, or the subject of the economy? The question is a central one for the professional storyteller, a question that informs and defines our relationship to our technique and our trade, a question that breeds a host of others: What place to make for the dominant forms? What place for the ruptures with that form, pointing toward the unresolved and unresolvable dilemmas of contemporary and eternal life? How much to offer up the lie that character can be defined by a list of traits? How much to defy the lie and risk a character whose fathomless contradictions may cause the consumer a stomachache? Invariably, the responses from the margins are not fitting for us who must live in the middle. But it doesn’t mean the questions are of any less moment, for in the end, the questions are about how to give life to work, and the workable answers to these questions are directly correlated to the audience. How it sees itself, how we see it, and fundamentally, what the audience craves from its stories. As such it is not only a moral matter for a storyteller, but a matter of his or her financial future.

9

What does this have to do with dialogue, if anything?

Only this:

That in a hegemony of images, the spoken word can still be a portal into a different register of aliveness and mystery. It is said that we hear before we see. That the Lord appears more readily to the ear than to the eye. That the act of speaking to another begins the rupture of that self-enclosed membrane from which we are all seeking some escape. If one of the first casualties of the age of industrial storytelling has been the theatre, then perhaps it is by recourse to the notion and experience of the spoken word; to the dialogue that embodies it, and which it engenders; to the listening that it requires of us as craftsmen and consumers; perhaps it can be the beginning of an understanding why the theatre still has life to breathe into us.

March 2012 / St Louis – Chicago – Harlem

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

A bracing piece of discourse on status v.s. contract, and an articulate encouragement for those of us fortunate (or perhaps stupid) enough to continue making a life in the theater. despite.

Thank you for this beautiful piece and for bringing it back to the word: "That in a hegemony of images, the spoken word can still be a portal into a different register of aliveness and mystery." Thank you, Ayad Akhtar.

The deepest eloquence of dialogue

is rendered through the seeming flow

of an unforced effort-

like glittering sunlight on water,

making its impact upon mind and heart

through a grace not wholly understood,

revealing something fresh and necessary,

unexpected,

a gift of something magical in the mundane

I would like to share a poem, "The Way," written by Albert Goldbarth:

"The sky is random. Even calling it "sky"

is an attempt to make meaning, say,

a shape, from the humanly visible part

of shapelessness in endlessness. It's what

we do, in some ways it's entirely what

we do—and so the devastating rose

of a galaxy's being born, the fatal lamé

of another's being torn and dying, we frame

in the lenses of our super-duper telescopes the way

we would those other completely incomprehensible

fecund and dying subjects at a family picnic.

Making them "subjects." "Rose." "Lamé." The way

our language scissors the enormity to scales

we can tolerate. The way we gild and rubricate

in memory, or edit out selectively.

An infant's gentle snoring, even, apportions

the eternal. When they moved to the boonies,

Dorothy Wordsworth measured their walk

to Crewkerne—then the nearest town—

by pushing a device invented especially

for such a project, a "perambulator": seven miles.

Her brother William pottered at his daffodils poem.

Ten thousand saw I at a glance: by which he meant

too many to count, but could only say it in counting."

Ayad Akhtar, you have touched on the core principle of the theatrical way. In light of theatre's myriad physical manifestations, we must ever accept that the word is equally physical, whether as incantatory lines on a page, or as vibrations arriving to the inner ear and evoking manifestations in the mind. It is through the word we irresistably find ourselves, to use Roger Scruton's phrase, "effing the ineffable."