How much present? Romanian theater in (Eastern) European context

In any culture the past is present in its values, practices, institutions, and hierarchies. Looking at the present Romanian performing arts landscape, this is very true. One could say, the past is too much present today. The theatre system of the communist era (1947–1989) of state subsidized theatre buildings with (big) companies and a (rich) repertoire is almost unchanged, as is the case in most other Eastern European countries. Does this constitute a success or is something still missing from this landscape?

Censorship after 1972 anticipated any public presentation of a show, since the “mistake” of opening a problematic performance would call for banning it, and banning would turn into a scandal, which the communist regime wanted to avoid.

The communist era unwittingly created a very rich theatre culture (among the other art forms). One could say the less personal freedom behind the Iron Curtain, the greater artistic values were produced in art and culture. Although censorship in the Ceauşescu era in Romania was much tougher than in any other Eastern European country, lots of artists of the seventies and eighties successfully created works that made it to the stage. Censorship was already at that time a set of ideological expectations, which were never publicly admitted or declared. Censorship after 1972 anticipated any public presentation of a show, since the “mistake” of opening a problematic performance would call for banning it, and banning would turn into a scandal, which the communist regime wanted to avoid.

In 1972 Lucian Pintilie’s production of Gogol’s The Inspector General was banned under the mask of the people’s will (a short notification published in the central party newspaper announced that a large group of people felt offended by the performance). The system could not allow such mistakes. Careful ideological party committees were eyeing first the repertory proposals of the theatres, then the scripts, then the rehearsals, until the shows became “party proof” and could be opened. These processes could sometimes take many months, even years. In the beginning only the texts—plays, scripts—were examined, but as supervisors realized that theatre communicates not only by text, anything else could become—and did become—a subject to be edited. The text was scrutinized first, and especially contemporary plays had to go under very strict examination (contemporary texts were the most important tools of ideological education). Contemporary playwriting—although theatres had some successes in passing certain texts—was the most difficult to get past the censors, so world literature or classical Romanian texts became more prominent. As everyday life worsened in Romania, food, public services such as electricity, water, and gas started to disappear. Anything with a concrete reference to these problems could become an issue for the censors. But also paradoxically symbolism was something censors were afraid of as well. Symbols could have any interpretation, or a subtext. A reference to cold on the stage could have a double meaning—criticism of the system or a reference to people with no heating in their homes. Costumes, stage design, lighting, music—everything could be a matter of double interpretation and thus of censorship. By the early eighties, theatres no longer had a guaranteed state subsidy and were forced to become self-sustaining institutions.

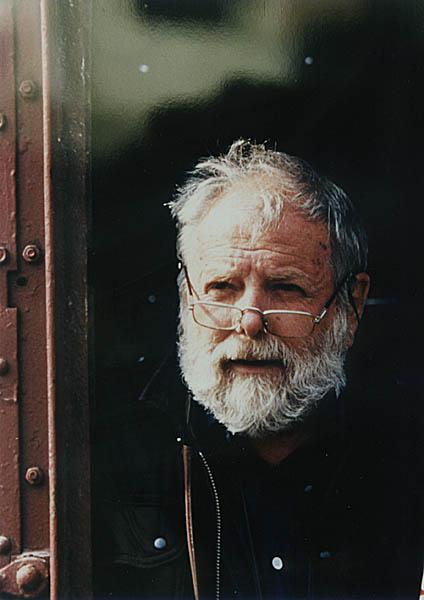

But still this was the era of great Romanian theatre. Under such conditions great performances were born, including reinterpretations of classical texts with a language of symbolism and universal values, often, reflecting a tragic view on existence. Romanian theatre had left behind stage naturalism. The high and artful theatricality of Romanian theatre of this era was its brand (which had very little international impact of course, since theatres did not travel). This era also produced a great generation—or probably more than one—of big directors, Liviu Ciulei, Lucian Pintilie, David Esrig, Andrei Şerban—all of whom left the country.

Theatre was a place of hope, normality, human values; a place for reflection and communication with audiences, providing an important societal role and impact. The theatre was also very popular. It was a form of escape through art. Whether such a theatre of opposition—critical of the prevailing ideology and lack of freedom—was the exclusive form of Romanian theatre, is questionable. Many theatre institutions preferred to present shows of “opportunism” with no spiritual or ideological conflicts, no critical attitude—many theatres were simply forced to do so.

This “theatrical theatre” had another source of inspiration, separate from its inner development as a specific form of art. One of the most important directors of the era, Liviu Ciulei, announced a program in 1956 in an essay, or rather a manifesto, called The Theatricalization of Theater Painting. In this small piece of writing he was calling for replacing stage naturalism with a “fantastic world,” an “imaginary universe,” doing things “different from the immediate reality,” creating poetical and dramatic images. Ciulei formulated the essence of Romania theatre language, dominant until 1990 and after.

The reason that such an artful, “arty,” theatrical, but also artificial theatre language was created was because the representation of the “the real,” the immediate reality was impossible: any reference to the “real” being dangerous and forbidden. (Interestingly, Hungary, with a much milder and tolerant communist regime, created its theatre brand in “small realism” or “microrealism,” penetrating into the small details of everyday life, and reflecting through that the conflicts of life experiences.)

After the social changes of 1990, most Eastern European theatres found themselves in a longer (generally, one decade long) crisis of the new social context. New forms of media and entertainment emerged and created a strong competition to theatre, threatening theatres with the loss of audiences. Most theatres turned to entertainment, considering this as a possible escape from the puzzling reality in an effort to compete with new media and television.

The Romania of the nineties, struggling for a decade to make a real turn toward democracy, was a moment of crisis for the public theaters and the notion of the public sphere in general. Parallel with performing arts, public media started its long and yet unfinished journey of a search for an identity among the big flow of the commercial media.

The role of theatre and its amazing importance created in the worst of circumstances was clear and unquestionable until 1990. After 1990 the question of the theatre’s role was very rarely raised. Romanian theatre continued its great practices of very theatrical, artful productions generally based on “big texts” of world literature, directed by directors of the previous era or new ones continuing the old practices. The social or societal community and communicative role of theatre, its criticism of an existing social/political environment—all these questions so evident until 1990—were lost and no longer raised, as if the questions had become pointless. It looked like the only role of theatre was to produce art, sometimes understood as “Art,” valued higher than reality, life, concrete human experiences, community, etc. The “old style” of escape (or even salvation) through art became gradually an escape into art, or an escape from reality.

Very often art for art’s sake produced high quality acting and interpretations of world literature, but produced very few Romanian texts, which should have dealt with the questions of Romanian identity and social context. For someone looking in from the outside, considering that a theater culture is part of the whole society and this should be reflected on the stage, this “big old” Romanian theatre often looked and still looks very nonspecific, with no time/space anchors or cultural context. Sometimes this means theatre that is spoken in the Romanian language, but without a real context for where it was created.

Or, to put it simply, forms remained unchanged, while the context was definitely lost, and a new context was not found, and was even often rejected. But the “old” form very often was still able to produce great spectacle, of course, like Silviu Purcărete’s Faust or Andrei Şerban’s (the Romanian director with an American career) Uncle Vania. But these were shows combining big Romanian theatricality with contemporary Western European practices—these generally being theatre productions of a huge scale, operating from a Western perspective.

There are two reasons why the social/societal content of theatre was—and still is, sometimes very vehemently—rejected in Romanian theatre practice. On one hand the social context (the “reality”) itself became much more complicated after 1990, and very often fragmented, exaggerated, and distorted by media. Social and existential problems were much less visible, and the social change from communism to capitalism was itself a trauma. The other reason is that the whole theatre institutional system remained basically untouched, unreformed in the new era. A space for new work to appear remained very narrow (one would say as narrow as in the communist era). Young artists and groups searching for new forms and content, with new working methods and new audiences, still have very little institutional and financial space, and are often almost invisible on the big map of Romanian theatre.

Romanian public theatres remained untouched by the European theater trends of the nineties—contemporary playwriting, collective writing, devised theatre, postdramatic theatre, documentary theatre, or contemporary dance. These trends are mostly present in the small independent field—one not linked to public theaters and big companies, and not having repertoires. We are looking more closely to a social content, such as the question of the role of theater in communicating with its audience. Important and internationally visible values are created in this field (i.e., works of Gianina Cărbunariu, often in cooperation with public theaters, or from the new directors’ generation, such as Radu Afrim’s work).

But the struggle of independent Romanian theatre comes from the resistance and the inertia of the “old.” It is definitely a moment of transition, in which we will have to ask two major questions: What is the role of public theatre (as distinct from the commercial theatre), what does it mean to “serve” the public, and where is the space for new work? Presently it looks like the first question is very rarely debated, and the second meets much passionate resistance, and receives too little moral/financial support from the decision makers and large institutions. Looking at Romania’s representative theatre festival, the National one, none of these questions are very present. But the current debates about the National festival—what is a national festival that has little representation of independent work—suggest that all these questions are sooner or later unavoidable.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here