Letting the Love Love you

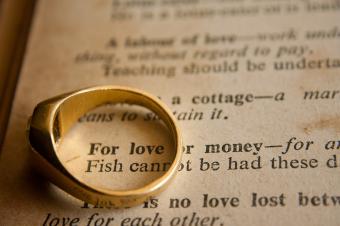

Navigating the Gray Areas of a Love or Money Industry; Part One: Finding Love

In a three-part series, Danielle Rosvally investigates the meaning of “professional” and “amateur” theater, and proposes a model to encourage healthy dialogue between the two.

Last year, I found myself in a bad situation. I was working as an actor on an unpaid dream-role project. I assumed that the project was professional. The project assumed that participants understood its amateur status. I expected industry complimentary tickets, a resume byline, and a product to which I could invite colleagues and potential future employers. The project delivered membership fees to the producing organization, incomplete production staff (actors had to stage-manage themselves), and the standing requirement for prop and wardrobe donations due to insufficient budget. Moreover, it continually laid on last-minute time demands, which I was expected to accommodate regardless of outside professional obligations. My fantasy project had become my personal hell.

As theater-makers, we make theater. As artists, we make it incessantly, heedless of obstacles. As professionals, we require compensation of some kind. Since most professional theater-makers are artists first, the accepted form of compensation often varies. As playwright and performance scholar, Meron Langsner posits, the professional artist takes on a project intending to be recompensed by either one of two cardinal draws: love or money.

There are many problems with an industry that functions on the “love or money” model. In theater, this practice is most commonly expected on the fringes of the trade; the places closest to the edge of professional status. More often than not, it is the small mom-and-pop theater or the experienced-but-not-mainstream professional artist who gives and receives of time and resources on the basis of love, or who is asked to work on projects without the promise of financial compensation.

There’s no escaping the fact that monetary transaction is a classic and accepted hallmark of professional stature. But since theater professionals are willing to regularly operate without it, we cannot then use it as the sole benchmark of professionalism within the theater industry. That leaves us in an odd predicament: without the standard indicator of status, how is a theater-maker able to identify his level of involvement with the theater? And how is a project able to be similarly classified?

The stakes are larger than they may at first appear. In addition to the nearly unspoken stigma about professionals working in the “minor leagues,” without a clear understanding of what those leagues constitute it is very easy for an individual to sign himself up for the wrong kind of project. An audition is an implied contract; at the audition an individual commits to giving her all to an enterprise. But what if, on the basis of a communication error due to unclear industry boundaries, your “for love” project isn’t ready to love you back?

In theater, the line between professional and amateur can be very hazy. For a case study, consider this instance: a small Boston-based company hires me to perform a leading role. Their budget is minimal and I will receive no monetary compensation for my time. I am then asked to perform the same role in a community theater production with similar expectations of recompense.

Even though the community theatre play isn’t necessarily “professional,” I am still expected to attend every rehearsal. I am still expected to know the same number of lines. I am still expected to give the same amount of time and devotion to the rehearsal and performance process as in the professional production. So where’s the line?

The community theater show is in a bigger house than the professional show. They both charge for tickets. More people come to see the community theater performance than the professional one. The community theater has higher quality sets/costumes/props because they have a larger budget. Where’s the line now?

There are many problems with an industry that functions on the “love or money” model. In theater, this practice is most commonly expected on the fringes of the trade; the places closest to the edge of professional status.

As professional theater-makers, we are all too quick to volunteer our time (not just to amateur projects, but to projects in general as Kenny Steven Fuentes has observed). We do this based on a number of theoretics: that actors will never be paid no matter the size of the project and so may as well perform for free, that demanding pay will yield an actor less work and gain him a reputation for being “difficult to work with”, and beneath all this the tacit assumption that an actor’s work is not worth paying for. The vast theatrical work ethic (especially from someone who identifies himself as a “professional” and thereby approaches every project with the utmost professionalism) puts us in compromising situations. If we truly work for love, that love can blind us to our own boundaries and cause us to violate not just our personal artistic integrity, but also our healthy relationships with the amateur theater community.

If a professional is already willing to donate his time to a project, what else will he be called upon to donate? Personal items (in the form of props/wardrobe)? Connections (in the form of requirements for cast members to sell ad space in the playbill)? Money (in the form of membership fees, expected/required cast ticket sales, etc.)? Should the amateur company be upset or hurt when the professional refuses to cancel vacation plans to attend rehearsal, does not assist in locating costuming for himself/others, or is not able to attend extra rehearsals due to other obligations?

In no other field is a professional who donates his time required, expected, or asked to give more. A doctor working at a free clinic would never be upbraided for not being available to work on a Sunday. A carpenter donating time to building houses for flood victims would not be required to stay past his allotted work window, especially if he had a paying job to attend.

Without some definition of terms, it is impossible to discuss the interplay between amateur and professional within the theater world. My dream-turned-nightmare project would have had much less sting if there had been some easy way for myself and the theater company to define our expectations of each other. Establishing a dialogue between the professional and amateur theater communities is possible, but only if we can first establish where these communities begin and end.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

This is a fantastic piece. The reverse is also true, however: simply getting paid does not a professional experience make. I have been involved in shows where I received financial compensation and as we went through the process, the expectation became that we as actors would pick up the slack for designers and others who either dropped out or didn't do what they were supposed to.

I had these same internal dilemmas in the Seattle area for the last year while finding acting work. The distinctions seemed only to be that "professional" companies had staff and regularly hired artists with some form of theatre training while "amateurs" didn't necessarily (though even that rule was far from concrete).

Also the caste between Equity and non-Equity professionals complicates the matter further, as does whether an institution is a LORT or CLO house or only grants guest or short-term contracts - or only hires non-Equity professionals. How can we call ourselves professionals if we're willing to forego income?