Teaching Playwriting in the 21st Century

Every citizen has at least one dramatic arc that is her or his life. Some are so agitated by it that they care to write it as a play. Spoken text gets separated out from movement and action, lights cue up here while sound punctuates or moods up the moment there. A three-dimensional space is posited and blueprinted on the page and collaborators help craft a performance where community and the curious can witness; and somewhere along the way, a worldview coalesces, describing our social moment through the writer’s most current lens—be it engagement or entertainment, or in the instance where scholar and market intersect, both.

Playwrights need mentors, esteemed and experienced professionals, who can help guide the journey of creation. These mentors teach through the example of their careers as well as their work in classrooms, which can encompass undergraduate courses, MFA in Playwriting programs, community outreach and private workshops. Playwriting pedagogy develops when methods and philosophies gain traction through praxis. Playwriting teachers pass along their approaches to the next generation and these students one day begin their teaching careers, applying these lessons with their own added perspectives.

The teaching of playwriting involves a myriad of approaches, strategies and philosophies in midwifing a play into being. There is the finding of voice, the actual writing of the play, the development towards production, the production itself (which is the completion of the writing of the play and usually outside of the playwright’s mind). Subsequently, for the sake of our capitalisms, there is the play’s market value, which, if one careers as a playwright, measures future livelihood. If one doesn’t pursue the professional playwriting life, there are applicable skills such as understanding citizen character through action and/or spoken language as well as identifying the complexity of conflict towards possible resolution.

Teaching playwriting in the twenty-first century presents new challenges to cultivating past traditions while incorporating new developments in the field and addressing an increasingly globalized society. Playwrights who teach today must address the areas of voice, liveness, and contradictions as they train tomorrow’s writers for the theatre. How do we empower a writer’s voice? How do we teach liveness in a technologically mediated world? How do we encourage the contradictory skills of solitary creation and collaborative expansion? How do we help students engage with the conundrums such as marketplace versus art form? Responses to these questions will endlessly vary; however one way to gain insight is to ruminate on and engage with these issues so that each writer can arrive at her or his unique pedagogical approach that will help train our future dramatists.

Playwrights who teach today must address the areas of voice, liveness, and contradictions as they train tomorrow’s writers for the theatre.

Voice

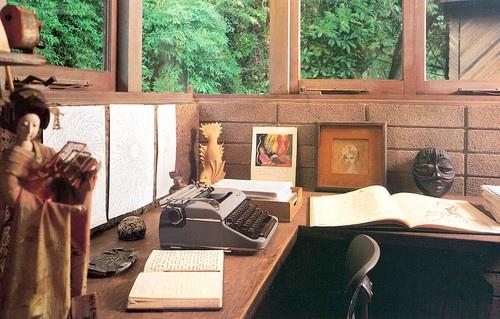

The word voice comes from the Latin vocare meaning to call or summon. To call forth vibrant, original writing requires the creation of a safe space in which to explore, discover, search, experiment, and expose, proclaiming unique perspectives with an initial emphasis on process not product. Maria Irene Fornes, a master teacher who trained a generation of playwrights through her INTAR Playwrights Workshop, approached creating this space by emphasizing the importance of the body-mind-spirit connection while utilizing methodologies such as yoga, visualization, collage and scenic design. This approach can empower the writer to create by drawing upon her or his unique physical and internal resources. Paula Vogel, an avatar of mentorship who trained a generation of playwrights while teaching at Brown and Yale Universities, often begins the school year with a “Bake-Off” where all the writers are given various prompts to incorporate into a play which must be written in the pursuant forty-eight hours. The students then gather to read through all the new creations. Often a seed for a larger work will arise from this “Bake-Off” play. These two mentors have nurtured the voices of many award-winning playwrights, their approaches encouraging creative abundance and dismantling notions of scarcity.

Liveness

Technological simultaneity now informs daily life. A click of the mouse can bring connection, opportunity, heartbreak or humiliation. We’re writing dialogue all the time in e-mails, in texts, in tweets, in posts, in our public voice, to be consumed, not necessarily live, in that mediated space. We communicate and connect, keeping in touch without that next level of investment in live voice (and not necessarily with an authentic interior) with many others at a time. We are instant characters, messaging instant scenes—depth is possible, but speed trumps attention.

Writing a play to be performed by live bodies, for live bodies seems antithetical to this current mediated age yet may provide a needed antidote to this attention-deficit, multi-tasking, hyper-linked moment. Teaching playwriting in our age means being willing to be counter-cultural, to demand a deft quality of attention and to develop an ear that hears and responds to language. Entering the experience of another for a period of minutes and hours may begin to grow empathy. Even within the classroom, as playwriting students read their work aloud to one another, perspectives can shift, with new contexts arising, and so a sense of artistic, aesthetic and cultural awareness can be nurtured.

Everyone maintains a singular presence “out there,” sharing, finding affinities, the Likes, its tabulations, attuned to the sounds of clicking, typing, thumbing. What could be a new icon instead of a thumbs-up “Like.” Perhaps “Wonder”? Playwriting teachers address all this with their writing exercises: breaking the rhythm, getting out of that public character’s voice, filling the empathy gap, reframing the questions to think towards answers anew, acquiring skills to comfortably live with unknowns, trafficking in mysteries and their agitations, their wonders.

Full disclosure: We both are Fornesians. We write in a land where the structuralists rarely tread. We innately subscribe to the transcultural model, where biculturality is organically drawn, and mind’s center can be shared and acknowledged through more than one dominant perspective. We understand that structure is essential; however teaching which privileges structure often tends to be linked more to product than process, to imitation than originality, to marketability than individuality, to a TV staff job or screenwriting career than a life of theatrical experimentation, freelancing and fellowships or grants.

García-Romero’s Writing Exercise

I began writing plays in college to give theatrical voice to my cultural world and its habitants that I longed to see on stage. I then studied with Fornes before and during my MFA in Playwriting training where she inspired me to delve more deeply into my playwriting practice. If I had to synthesize some of the key elements of the craft that Fornes taught me, they would be:

- Attention to inner mystery can often inspire the genesis of rich play material.

- Character creation provides the first essential movement towards writing a new play.

- Ultimately, characters’ unpredictable paths shape a play’s structure.

I always aim to help my students delve more deeply into character. How does a character behave in ways that are surprising, idiosyncratic, unnerving or seemingly irrational? How can a character become more complicated, multi-layered, intriguing and mysterious? How can our characters seek adventure, danger, love, passion or transgression? An exercise I teach (adapted from Fornes) that addresses these questions draws upon the transcultural notion that characters often navigate more than one world simultaneously. This exercise works best after initial character creation. I call it Animal Instinct:

- Visualize your character. With eyes closed, picture a character you’ve already created. Once your character is in your mind’s eye, observe all the aspects of your character. Look at the hair, face, eyes, nose, mouth, body, arms, torso, legs, height, weight and shape. What kind of clothing is your character wearing? If your character is wearing shoes, what kind of shoes? Once this character is clear to you, open your eyes and draw a picture of your character.

- Visualize an animal. With eyes closed, picture a wild animal. Once the animal is in your mind’s eye, picture all aspects of the animal. Look at its body, appendages, skin, teeth, hair and coloring. How does it move through space? What sounds and/or gestures does it make? Once your animal is clear to you, open your eyes and draw a picture of your animal.

- Visualize your transformed character. With eyes closed, now picture your human character standing directly in front of your wild animal. Picture your human character merging with the animal so that the character remains human but is imbued with the animal’s gestures and qualities. Picture this transformed human character in a specific location interacting with a second character. Where are these two characters? Is the location interior or exterior? Is it day or night? Who is the second character? Picture all aspects of this second character. When this is clear to you, open your eyes and begin to write a scene between your transformed human character and the second character in this specific location.

After writing for about ten minutes, stop. Ask for volunteers to read. Have the student describe his or her human character and wild animal and then read the scene. Students do not need to share their drawings although they can if they’d like. This exercise can be particularly helpful for first-time writers as it can help liberate received notions of what a character is or can do. Lastly, like Fornes, I always write alongside my students during the exercise. I gain energy from the creative focus in the room and often find inspiration for my plays during these in-class explorations.

Tuan’s Writing Exercise

I entered theatre as venue for the First Amendment—an attempt to write myself into US culture on my own terms. But even more importantly—I sought freedom to imagine myself beyond expectations.

I entered theatre as venue for the First Amendment—an attempt to write myself into US culture on my own terms.

One writing exercise that I administer relies on impulse and intuition to mine the interior and asks for patience and faith: what does one do when nothing comes through? It also feels like democracy, where everyone sits equally with their writing selves, expressing from their own voice, but prompted randomly by the collective. Each work is regarded with attentive ears and open hearts; for this moment, it is a singular culture activated by the minds in the room. This exercise works particularly well with first-time writers, but because of its random nature, any level of writer can profit from it and the exercise can be done ad infinitum. I call it the Prompter Exercise.

Each writer is given six pieces of paper (3”x 4”)—it is important that the paperettes are all the same size (I usually take scratch 8 ½” x 11” and tear up eight per page). You will need a hat or a box (any container) to collect each round of prompts.

Round 1: On the first paperette, write an ACTION. Once this prompt is written, the paperette is folded in half and the number ‘1’ is written on the outside. The hat or box goes around and all of the writers’ number ‘1’ prompts are collected. On a table (or any space you can have six piles of paperettes) empty out the hat or box and put this pile of number ‘1’ prompts aside.

Repeat for Round 2—PLACE, Round 3—PROP, Round 4—A SECRET, Round 5—FIRST LINE, Round 6—LAST LINE. (Of course, try out other prompts). Once you have the six piles, you now redistribute the prompts so that each writer will have six disparate prompts, not their own. Yes pile ‘1’ goes back into the hat or box and what once was a collecting is now a giving back. As each writer picks a prompt, make sure he or she does not look inside. (This is actually a mini practice in restraint, and the pay off comes when they look at all six prompts at once). Also, the picker refers to the number written on the outside so as not to pick their own. Repeat until all the piles are distributed (and all that restraint kicks up the energy).

When you give the signal, the writers will look at their prompts and then write a scene using all of the prompts. Before you start, remind the writers that it is okay to sit there and have no idea how to make the disparate elements work. Really privilege the space of not knowing, having patience, having faith, looking at each, quickly indexing through the possibilities, maybe responding to the prompt which leaps out, going with the impulses, relying on the other prompts when one gets stuck. This chance allows oneself to go with intuition, figure out what the scene is halfway through—or maybe not until it’s done. It is a process, so it’s messy, but once the scene is written and read out loud, the writers have an extra perk in seeing how other writers handle the prompts that s/he has given to the group.

Towards Howling

Writing a play begins as a solitary moment and concludes with a public performance. Internal gives way to external. A certain malleability seems required, an ability to shape shift from monk to master of ceremonies. Teaching these aspects is an ongoing dialogue about the process, from page to stage, and only in this way can the young writer build the muscle to develop a work from the fragile first idea to a stable final theatrical form.

Ultimately, a teacher can inspire by seeing beyond the work and contextualizing the play’s potential and/or contribution to the United States (and world) culture not to mention the playwrights’ own body of work. Each teacher has her or his forte(s) in the development of a dramatic writing—there are as many ways as there are plays. We are excited to start off this conversation and look forward to many, many rounds of howling about the teaching of playwriting.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

I am a budding playwright/middle school teacher. This article has helped me reflect on the ways I will teach playwriting. Thank you!

Fantastic article, Anne and Alice! I'm going to use both exercises the next chance I get. What they have in common is the invitation to the writer to abandon him or herself to not knowing. Keats' "negative capability." The artist's ability to live with uncertainty. We teach them how to embrace mystery. Yes.

This is great! I'm going to try these writing exercises with my students. Thanks!

Teaching an art with ancient roots has a subversive quality today. We pass on

treasures we are in danger of losing, such as: adding an element of soul expanding chance, cultivating hybrid/particular identity, challenging the myth of scarcity, fostering empathy. I’m so glad that Tuan/Garcia-Romero, dear compañeras/teachers/leaders/guides/brilliant playwrights both…are keeping the flame of Fornes lit….reminding us of the what we lose when structure is overly privileged….and the inestimable gifts of privileging not knowing, patience, faith instead. Thank you.-- Elaine Avila

Thank you, Elaine, for your beautiful response here and for the reminder that taking chances in the writing while leaping into the unknown is a soul expanding privilege!

Really enjoyed and appreciate the article. Thanks for taking the time to share.

Great article, thanks!