Thanking the Directors

It’s American; you move. That’s what Americans do. You change houses. You move, you change. The furniture’s yours; you hope that, in some way, its disparate styles and combinations represent you, your larger life. But on any number of scheduled occasions, over a lifetime, you stand in a container of empty rooms and wonder why you’ve done what you’ve done: moved, relocated, upscaled, downscaled.

A truck that could just as well be carrying half a circus—it’s that big—pulls up in front of where you are. You open the front door. Two guys in coveralls are sliding huge garage-like doors open. The inside of the truck looks like a yard full of flattened demolished autos: there are no spaces in-between; there’s no light. Everything’s covered in ash-colored, quilt-like cloths. And then the two guys in coveralls start removing the-furniture of your life, piece by piece, setting all the heavy stuff under the lips of dollies which—now that they see your door is open and you’re aware of them—they begin rolling toward you. “Where do you want this?” they ask. In theatre, we call these guys directors. And thank God for them! They’re invaluable.

Like the van movers above, it’s the directors that have made me feel they wanted my new house to be the best house it might be—given its furniture. They’ve noted when a given space seemed too empty or too crowded. They’ve suggested more color…less color. More light…less light. They’ve said things like: “There’s a lot of just talk in this scene. And I like the talk, but… Think about what your characters might be doing…while they’re talking.”

The first of these directors was a third-year director at Yale Drama School—Chuck Vicinus. I was an entering playwright, and I’d dropped a one act, entitled Merry Old Soul into a box the more seasoned directors perused looking for possible afternoon lab theatre productions. Less than a week after I’d deposited my script, Chuck called. He’d read my play, he liked it, might he direct it? Why ever would I say no?

In Chuck, I discovered the director qualities which taught me how best to work and write. They were the qualities that I would have the good fortune of finding in a handful of other directors over my more than fifty years of writing plays.

Chuck was a close and respectful reader. He directed three of my plays at Yale and several in professional theatres thereafter, and in each instance—at that point when we would first sit down and “talk”—he knew more about the play than I. Though—through my own study and close-reading—I have an acute sense of form, I don’t plan plays formally. For the most part, through several drafts of any play, form is, at best, an informed instinct.

The gift that a close and respectful reader/director gives a playwright is the message: I’m drawn to this play to such a degree that I want to understand every word and moment that is written. The close and respectful reader/director is deeply engaged by the script but is never prescriptive or appropriative. Such a director would never say, “If you’re doing A in your first scene, you can’t do B in your third scene. Fix it.” Such a director uses close reading to respectfully illuminate the playwright’s script to the playwright in such a way that it impossible for the playwright not to “see” that which is compelling and that which is not yet done which might make the script more compelling.

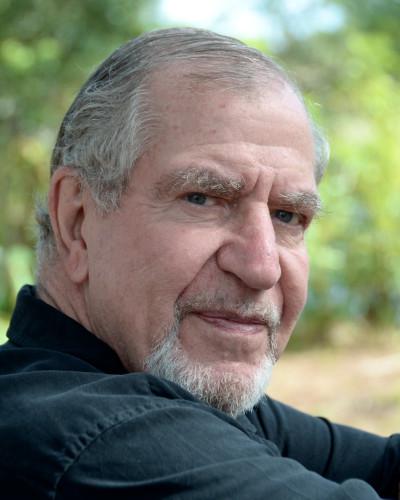

Who are my “handful” of directors to whom I’m grateful? I’ve mentioned Chuck Vicinus. Then, in no particular order: Jon Jory, who directed my plays/work at Yale, at Long Wharf and at Actor’s Theater of Louisville; David Chambers, who directed five of my plays at Salt Lake Acting Company and served, with me, in directing the Sundance Playwrights’ Lab during its first fourteen years; Rich Rice, who directed my plays in New Hampshire (3), Tennessee (1), Florida (radio play), Poland (1). In addition, Rich has been a tireless reader of my plays (and, sometimes typist). Kenneth Washington, who directed five of my plays in Utah—variously at the Salt Lake Acting Company, Theater 138, and the Babcock Theater.

Jon Jory would always honor a change I made, but he taught me to watch and wait. Playwrights can be impatient. They hate a scene on rehearsal Tuesday, love it on rehearsal Wednesday, hate it again on rehearsal Thursday.

Plays are unstable creatures. The slightest element in the room—a tired actor, a buzzing fly, the way light cuts through an uncurtained window, the playwright’s own security or insecurity—can shift the tone and dynamic of any play. Better to watch that which bothers you a second time and then a third, then a fourth. Jon—a legendary writer himself—loved writers, loved well-shaped words. I don’t remember whether at Long Wharf or Actor’s Theater that he gave an actor in one of my plays the request: “As an exercise: let’s drop the script lines between A and G. Instead: when you reach A, see if you can do what the lines now state. Try. Do the script instead of stating it…and then move on. Pick the dialogue up at G.”

Or all of these directors, the playwright’s words sacrosanct, were the last words. But all had embracing yet clear ways of asking whether all the words were necessary or in the right place.

See if you can do…instead of state. Of course! Jon was so right. Act! Don’t chatter! So I cut the lines, and the scene moved with much more physicality and momentum. He was trying to be illuminative, not appropriative. For all of these directors, the playwright’s words sacrosanct, were the last words. But all had embracing yet clear ways of asking whether all the words were necessary or in the right place.

Similarly, all had a nonprescriptive way of asking, “Might we have a few more words here to help us get from A to B?”

Rich Rice had been trained in music at Oberlin. He had a deep sense of musical composition, musical form. There is no question: Rich’s overlaying of his knowledge of musical structure onto his work on my plays has been an enormous gift. We’ve worked together for nearly forty years, and I’ve seen my plays become increasingly influenced by the musical knowledge Rich Rice has suffused them with. I’ve observed Rich listening to music in the process of rehearsing one or another of my plays. What he listens to is different depending on the script. Gentle and kind—Rich has never pedantically “schooled” me in the formal music theatre connection. Yet, through him, through absorption, I’ve gotten it. And over those years, more and more, with any new script struggle, I find myself listening: trying to find the right music, right musical shape, right music of words which might then become the right dramatic-shape.

And it was also through Rich that I learned most about the play-audience connection: that the audience craves the invitation to be in the story, in the action. The audience wants an open window—not a two-way glass. Here’s the situation which taught me. Rich was premiering my play, Fall Holiday. A week before opening we lost a cast member. Postpone the opening? “No,” Rich said. “We’ll open on the announced date and, at the given hour, tell our audience the situation. Tell them that they’re watching a runthrough rather than an opening, that we may stop and start. Invite them in. Be honest with them. Tell them we’d like their feedback when the curtain goes down.”

I was nervous. I imagined an angry audience upset they’d not gotten what they’d been promised. Still, I agreed. And Rich, of course, was right. The audience was animated. They loved being in. They leaned forward in their seats rather than sitting back. They’d been given a part in the evening, in the play, and they were eager to fulfill it.

Any audience to a play is in the room, is in the action. It’s a spatial reality. Best for any playwright—in his or her own way—to acknowledge rather than deny that. And it was Rich Rice who created the living situation that taught me that.

Kenneth Washington gave me many gifts, but the greatest was his insistence that a play is a living thing and the writing of it never stops. I’d worked with directors who—and it was reasonable—had certain last rewrite rules. Ten days, say, before opening, there were to be no more rewrites. It made sense. Many actors tremble at the sight of new pages.

But for Kenneth, a play was always new. Plays happened now. And now was new. For Kenneth, the notion of a rewrite deadline was unthinkable. Rewrites could occur and be assimilated a day, a week, after opening. And those rewrites could necessitate light changes. I remember a night when a new moment took place in the dark…because the person running lights wasn’t up to speed. For Kenneth, that was fine. It was interesting. And though I, myself, would never expect revisions to be honored and embraced that entirely, the approach did embed in me and in my writing the notion that, yes: A play is new. Always. And that was part of my writing obligation: to attempt to keep every moment of the play new.

And though the next statement of gratitude applies to all directors I’m thanking, it applies most to Kenneth. I am grateful that whatever I wrote—whatever was in process—would be embraced, responded to, and brought to life on a local, available stage. Will this ever get done?—with Kenneth around—was never an interfering question as I pursued the writing. The freeing of any playwright to just write is an enormous gift. And I am thankful to all these mentioned directors for that.

David Chambers—always so reasoned; always so calm—gave me the gift, ironically, of permitted wildness. Reliable and solid David Chambers’ central gift to me was something like: You are most compelling when you let your demons out, when you let your wild and unexplainable imagination do its thing.

David wouldn’t be so prescriptive as to say, “Be crazy.” Rather he would find that scene, those moments, in a script where I had let go, and he would say, “Here’s where I really get excited. I’m not sure, exactly, what you’re doing here, but could you do more of it?”

It was David who encouraged me to take on the Sundance Playwrights’ Lab. Sterling Van Wagonen had approached me on behalf of Mr. Redford and asked: Could I imagine a theatre lab along the lines of the film lab? Never ask a playwright to imagine! I said yes. But I had no managerial skills. So I went to David, showed him what I’d imagined and asked, “Could you do this with me?”

“This is wild,” he said. “This is crazy. I’m not confident we could pull this off.”

“But will you help me? Will you ground the things that need grounding?”

He said Yes, and off we went. For fourteen years: off we went. This is crazy.

The great lesson of theatre—for those willing to learn it—is, We are not alone. These are our stories, this is our family, look around—this is our town.

Thank you, David, for—again and again—encouraging me to be crazy and lowering any self-consciousness about my craziness to a low boil.

The great lesson of theatre—for those willing to learn it—is, We are not alone. These are our stories, this is our family, look around—this is our town. These are hard truths—especially in these times and given America’s incurably frontier mentality—to internalize. Theatre must be a potlatch. In theatre, we must give each other gifts, and be willing to pay attention as the gift travels—from writer to director to actor to designer—out and out and then back again.

It’s like those nights, long ago when we were children at camp and sitting around in a fire circle. And a story would start…and be picked up and grow and shift and turn, become silly, become frightening…until it came around again to he or she who’d begun the story—the story returning to its teller, like the wanderer to his tribe, and the better for it.

And the better for it.

And this is me—somewhere in that circle—thanking the moving men. Thanking the Directors.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Thanks for this. Really, really - thank you. We are all parts of the circle - the crazy, wonderful, stressful, exhilarating, magical circle of storytelling.