Jennifer Schaupp is a US-based adjunct professor, storyteller, and comedic improvisor embarking on a PhD in Creativity examining how applied theatre can enhance the English language learning process, mental health, and civic engagement of those new to the country. She presented a trial workshop “Gestural & Spoken Language as an Act of Personal Freedom” at the summer 2023 virtual Pedagogy and Theatre of the Oppressed (PTO) conference where she met Ghana-based applied theatre artist and University of Ghana professor Dr. Felicia Owusu-Ansah, who attended Jennifer’s workshop and also presented her paper “My Image, My Conscience, My Story: Image Theatre as a Gateway between Silence and Blast." Theatre of the Oppressed (TO) includes Forum and Image Theatre, two styles that involve everyday people embodying solutions to problems they're facing either through bodily-sculpted images or scene enactments—essentially a rehearsal for real life. There are so many different ways that founder Augusto Boal and other applied theatre artists, like Felicia, have utilized the form over the years. Jennifer was struck by how Felicia unearthed relevant social issues with the use of Image Theatre and connected with various communities in her country. Jennifer and Felicia sat down for an interview to discuss TO’s potential as an empowering theatrical form.

Jennifer Schaupp: Welcome, Dr. Felicia Owusu-Ansah! When we met, I was struck by the number of people you've worked with, the ways you've used TO, and just how much you’ve learned about the communities around you.

I remember during your conference talk that you said TO was not very popular in Ghana. I'm curious, how did you start to get people excited about TO?

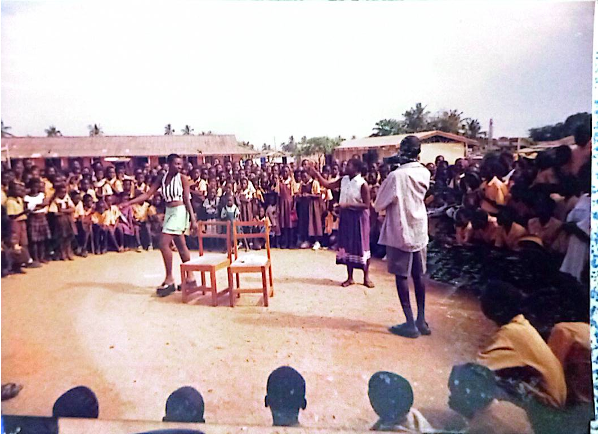

Felicia Owusu-Ansah: I teach and practice Theatre of the Oppressed. I use TO tools to explain concepts. For example, on the topic “Identifying Community Issues for TO projects,” I asked my students to take photographs of anything in sight for a class discussion. A student captured a photograph of a sculpture depicting a woman carrying a basket of cocoa, gritting her teeth while balancing her load with a baby strapped at her back. According to the student, he saw in the photograph an image, a theatrical item that is compelling and vivid, conveying his mother's spirit.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here