On the Builders

Marianne Weems in Conversation

Director Marianne Weems is the Spike Jonze of the theatre world. For the past twenty years as Artistic Director of The Builders Association—founded in 1994, she has directed plays that have skillfully sutured the conventions of theatre and the megabits of technology. A fluid alchemy of live acting and hyperreal images, Weems’ plays give the impression of being perfectly aligned with the spirit of our digitally drenched times. Under Weems’ stewardship, The Builders Association has established a tradition of producing cutting edge plays on the contemporary human condition; they have included the likes of Alladeen, a play on the impact of global technology on the denizens of New York, London, and Bangalore, and Continuous City, an exploration of human lives against the backdrop of transnational communication technologies.

In the following interview, Weems, who is also the head of graduate directing in the School of Drama at Carnegie Mellon University, talks about aesthetics, influences, pedagogy, The Builders Association, and her two current plays on tour: House/Divided and Sontag: Reborn. The former interweaves the foreclosure crisis of 2008 with an adaptation of John Steinbeck’s Dust Bowl era novel, Grapes of Wrath. Sontag employs Susan Sontag’s journals to give us a riveting bildungsroman of Sontag’s earlier years and her formation as an artist and intellectual.

Stila Nayak: What drew you to a career in theatre? How did you get started as a director?

Marianne Weems: I studied composition at Columbia University for my BFA and I really was just immersed in the downtown theatre world in New York City and started writing music informally for different companies I was attracted to, and mostly just serving as an Assistant Director to a lot of very important artists like Richard Foreman and The Wooster Group, etc. That was my informal education: being a dramaturg and Assistant Director at the WG for six years in the late eighties to the early nineties. The trajectory is to get away from school and into the actual work and apprentice yourself to people you are actually interested in.

Nayak: How did the Builder’s Association get built?

Weems: I had learned a lot about creating an ensemble through working with The Wooster Group and I essentially just wanted to start working with my colleagues. We began working on a project called The Master Builder which became the birthing site of the company and involved a lot of people who are still working with me today like John Cleater, who is the set designer for House/Divided and Dan Dobson who is the sound designer and Jennifer Tipton who did the lights—all people who have been working these twenty years on all our productions. It was a very formative experience because we were working very hard to incorporate media into story-telling and for the service of story-telling and that is essentially what we are still doing.

Nayak: What led you to the particular aesthetic that has become the hallmark of The Builder’s Association—the marriage between theatre and media technology? Did you know from the outset what kind of theatre you wanted to produce?

Weems: Because of my training in the experimental theatre world, I have always been very interested in the theatre as the moment, what actually is happening culturally and socially rather than looking at theatre in a historic or traditional context. In the early nineties, of course, it began to seem very natural and organic to include media in the productions because basically we are holding a mirror up to the contemporary world, sort of mid-revolution in terms of the mediatization of our culture and it has only become more so since then. So this idea of really reflecting what we see in the world as opposed to more traditional staging is what motivated the aesthetic.

When we first started a lot of people would say, “Is this theatre?”—Producers, presenters and audience members alike.

Nayak: In the nineties it must have seemed like you were ahead of the curve and now it appears that you are in step with the times. How do you see your journey over this period—has the taste for the kind of theatre The Builder’s Association is known for changed between then and now?

Weems: Because we have doing it for twenty years it seems like we are in step with the times. Over that period, our aesthetic has gotten honed and more refined and subtle. It is integrated into our story-telling in a way that is less about foregrounding the media. It has just become our language. That is a key component of all our work that we are on the spectrum between theatre and a complex mixed media form.

When we first started a lot of people would say, “Is this theatre?”—Producers, presenters and audience members alike. And our response at the time was, “Well it is taking place in the theatre,” and obviously all that has changed. The vocabulary has become so common both on Broadway and in opera and it is not a surprise anymore. We are working on a book about the history of Builders by MIT Press forthcoming in 2016 that I am very excited about. It is being co-authored by Professor Shannon Jackson who teaches at UC-Berkeley. One of the important things that Shannon is doing is tracing that trajectory of our going from being almost radical and cutting edge to working with a vocabulary that now is not surprising. But it is something we have honed, so I still think the aesthetic is quite extraordinary.

Nayak: This is a very interesting perspective of your journey. What were some of the questions that audiences in the nineties would ask?

Weems: A lot of people were saying and these are the questions people still ask, “How did you make this? How much did it cost? And what does it mean?” They just see the form and it is like a complete picture. The parts that are woven into it are still kind of invisible. It is this painful, painstaking, infinitesimal process of adding media, text, performance and really weaving it all together. That is just an ongoing conversation.

Nayak: Were you ever worried about alienating your audiences in the earlier period of The Builder’s Association?

Weems: We spent a lot of time in our early trajectory in Europe for several reasons. There was more support there for this kind of work, the vocabulary was more familiar to audience members and there wasn’t this kind of general resistance to our work. Obviously that has changed. We started touring in the States in 2003 or 2004 and we haven’t stopped since then. It’s definitely part of the theatrical vocabulary at this point.

The thing that theatre has going for it is that it is live. So hopefully that has emerged again as something of value in this completely canned culture. That is something that audiences will value regardless of their age.

Nayak: Looking back to the 1990s can you recount some of the hot cultural moments that spoke to this spreading influence of technology and would have inspired your work?

Weems: (Laughs) This is ancient history by now, but what was happening were these things called MUD (Multi-user dwelling) and basically they were the precursors to Facebook and any kind of online group activity like “Second Life” for instance. So the amazing thing about them is that they were all text-based. There weren’t any images. People would build “elaborate houses and castles” and describe things like, “You are walking down an endless hallway and going into a moat.” And it was all written. So people were trying to create this building online that was text based. So that is how old that idea is. That was in 93 or 94. Soon after that SIMS and “Second Life” started to really take off. So there was this moment of cultural collective unity that was in this very clumsy text based format. It is kind of interesting when you think about that vis-à-vis “The Master Builder” which was literally about building this huge, analog house but it was also about staging the network inside the house and that’s what our shows have been since then—staging a network. This is the interesting thing with our theatre company that we always have been drilling down what was happening with the rise of media in our culture.

Nayak: You mentioned the experimental theatre scene. Can you tell me something about the deep influences that have had an impact on your own work?

Weems: There was a whole hotbed of visual art that was taking place in the early 90s that both incorporated media and incorporated cultural critique. If you think of Gretchen Bender or even Nam June Paik or Judith Barry and Gary Hill—All those people were using video that was quite beautiful and also aesthetically quite refined but also capturing the moment of being overwhelmed by this mediatized culture. That I think was very influential for me outside of theatre—what was happening in the visual art and installation world.

Obviously the media is very performative in our culture and on the stage. And it is something that is seductive and you can easily be sucked into as both an artist and as an audience member.

Nayak: What is your vision for achieving a balance between performance and the multimedia elements within a play?

Weems: That is my role as a director and that is the responsibility of a director to balance the relationship between the presence of the performers and the presence of the media. So it is a delicate balance. Obviously the media is very performative in our culture and on the stage. And it is something that is seductive and you can easily be sucked into as both an artist and as an audience member. I think most of our work has been about creating this tension between the live people on stage and the world that surrounds them. And it is very much about trying to balance the two levels of performance.

Nayak: What about process? In terms of the elaborate production of House/Divided or Sontag:Reborn, how did you move from conception to building this entire world on the stage?

Weems: Good question. It definitely doesn’t start with a script. Our work usually starts with a concept and again something that is drawn from this contemporary moment. It is very idea driven—the theatre, the product. The dramaturgy is very important in terms of soaking all the elements with content. So for instance with House/Divided and all of our shows everyone is there from the beginning—the designers, the actors and dramaturg and me and whoever is trying to write the script and all the performers. We investigate the material together and then it takes these different forms.

So with House/Divided we started with the housing crisis which I was very interested in and the idea of a house (laughs). I was thinking about restaging Master Builders, but it became really clear that the idea of a house in American domestic space had changed since 1994. So we started with what a house is today. And that quickly led to Grapes of Wrath because that is so much about dispossession and the economic forces that motivates the American mother story of people being thrown out and on the road. So all those ideas were the stew that we pulled the piece from. A lot of very beautiful things came out of that in very different manifestations. So John Cleeter and Neal Wilkinson designed a set that basically was an old house. It was a foreclosed house that we cut down and repurposed and made into a theatre set. And our sound designer Dan Dobson made an incredible sound score, which is sort of playing with analog music in the way we are playing with the house. Then most importantly James Gibbs and Moe Angelos did write the script. But that was sort of like the last thing to come. Because what we all agreed on was that we were going to bounce between the two texts: The Grapes of Wrath and the material that was drawn from the economic crisis of 2008. James Gibbs really pulled all of these quarterly reports from the CEOs of banks like Lehmann Brothers. In large part that became the text, which is fabulous, and is woven through in counterpoint to Grapes of Wrath in an extraordinary way. All this comes from this idea of the dramaturgy being driven by the idea rather than we start with the script.

With the Sontag piece it was different because Moe Angelos started with the idea of working with her journals. I had known Susan. She was a mentor of mine and was on our board. So that was a personal piece, a personal journey to begin with. Essentially it became the same thing in that the media really served to tell the story. It is a dialogue between the younger Susan and the older one. It is very much about memory and representation and imagery.

Nayak: Since you are touring with both Sontag and House/Divided, what is the fundamental difference in the use of multimedia in both plays? On the surface, Sontag uses technology in a far more limited fashion and the focus is very much on Moe Angelos’ performance and her projection of Sontag’s narrative.

Weems: Sontag is really the only simple piece we have ever done (laughs). House/Divided is much more large scale in every way. I love the Sontag piece, but it is more of a chamber piece compared to a symphony, which House Divided becomes.

Nayak: What do you read or watch for inspiration? What media materials drive you to your own creations in theatre?

Weems: In addition to the visual artists I mentioned and of course the Wooster Group which was very instrumental in terms of looking at a deconstructive language for theatre, one of my biggest influences is The New York Times. I read it regularly. That’s my relationship to my source material is to find out what is happening day by day and globally. That is a weird answer but it is part of my artillery. Formally I have been very influenced by William Forsythe and Ariane Mnouchkine and all the heroic people in that world. Not so much by the content but by the form and scale per se.

Nayak: You mentioned you were in your fifth year of teaching in the School of Drama at Carnegie Mellon. Do you have any advice for young and aspiring theatremakers?

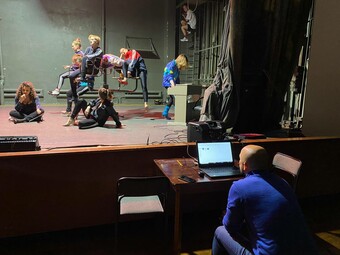

Weems: For people to hone their vision and to create something that is of interest to them the main thing is to get on your feet with the materials. One of the beneficial things at Carnegie Mellon is that we have built a big studio, a multi-media workspace and that allows students to actively sketch with video and other kinds of technology and live performers, and loosely move screens and cameras around, and experiment with the vocabulary. I still think the only way to hone your craft is to actually get on your feet and do it as much as possible. It is a balance between studio and seminar, which is really difficult in a lot of universities because space and technology are at such a premium.

Nayak: Are you guided by a particular teaching philosophy?

Weems: I always quote from the Iowa Writers Program. They open their description of the program by saying that, “We can’t create writers. We can only create better writers.” I think that is very true with graduate directing certainly. People need to come in with vision and some experience with the real world and my job is to challenge them to articulate their aesthetic. So, again it is sort of more of a studio-based practice. We certainly do look at a lot of work and we do look at the global context of experimental theatre. But again I urge students to learn everything on their feet.

Nayak: What’s next? What is happening at The Builders Association in the next few years?

Weems: There are two new shows we are starting. One is—which I can talk about—based on The Wizard of Oz. The show asks you to think of AR or Augmented Reality as a layer in the theatre to be a kind of Oz, which obviously it is in real life. That is very heavily in progress and we are premiering it next January. So that is the next thing in the docks. And then just working on general survival in the company. That’s the thing about arts in America. You can be relatively “successful,” but if you are in an off Broadway non-profit environment then it is always an uphill battle for funding. It doesn’t mean we want to stop doing it but it is really the state of things.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here